The Hypocrisy of "Floating Bars": Why Regulated Licenses are the Cleaner Path

Why does one hotel in Hulhulé enjoy a monopoly while global brands in Malé are sidelined? A look at the economic cost of inconsistent regulations and the case for a transparent licensing system.

These debates are difficult, but they are necessary.

First, I want to be clear about where I stand: I am a proud Sunni Muslim, and I strive to practice my faith in my daily life.

However, my views on the availability of alcohol and pork in select city hotels are not rooted in religion; they are rooted in the hard realities of economic diversification and market equity.

The Fairness Gap

A few months ago, I spoke with a senior executive from a major international hotel brand operating in Malé. His frustration was clear: “Why is a city hotel in Hulhulé (HIH) allowed to serve liquor, while we are not?”

From a foreign investor’s perspective, this is a glaring competitive disadvantage. When we invite global brands like Barceló (at Nasandhura) or Hotel Jen into our capital, we expect them to compete on a global stage. Yet, we deny them a revenue stream that their nearby competitors—and every resort in the country—already enjoy.

If a city hotel in Hulhulé can operate under these guidelines, why not a premium city hotel in Malé? The current policy isn’t just inconsistent; it’s unfair.

Regulation vs. The Black Market

We must also address the “floating bar” phenomenon. Currently, almost every local tourist island relies on safari boats anchored offshore to serve alcohol. This “loophole” economy doesn’t just inconvenience tourists; it fosters a thriving black market and creates a regulatory vacuum.

By allowing established city hotels to serve liquor under strict, specific licenses, we bring this activity into a controlled, taxable, and transparent environment. To be clear: I am not suggesting every guesthouse on every local island should have a license. I am advocating for high-standard, regulated licenses for city hotels to displace the shadow economy with professional oversight.

To address both economic needs and social sensitivities, the license should not be a “blanket” permit. It would likely require:

Zoning & Visibility: Alcohol and pork must be served in designated areas (like a rooftop bar or enclosed restaurant) that are not visible from the street or public areas.

Passport-Only Service: Serving only foreign passport holders. Maldivian nationals (including those with dual citizenship) would be strictly prohibited from service.

Employment Restrictions: Only expatriate staff would be allowed to handle, serve, or manage the inventory of alcohol and pork.

Digital Inventory Tracking: Real-time reporting of sales and stock levels to the Ministry of Economic Development and Customs to prevent leakage into the local black market.

Security & Surveillance: Mandatory 24/7 CCTV in storage areas and bar entrances, with data accessible to the Maldives Police Service upon request.

The Occupancy Crisis

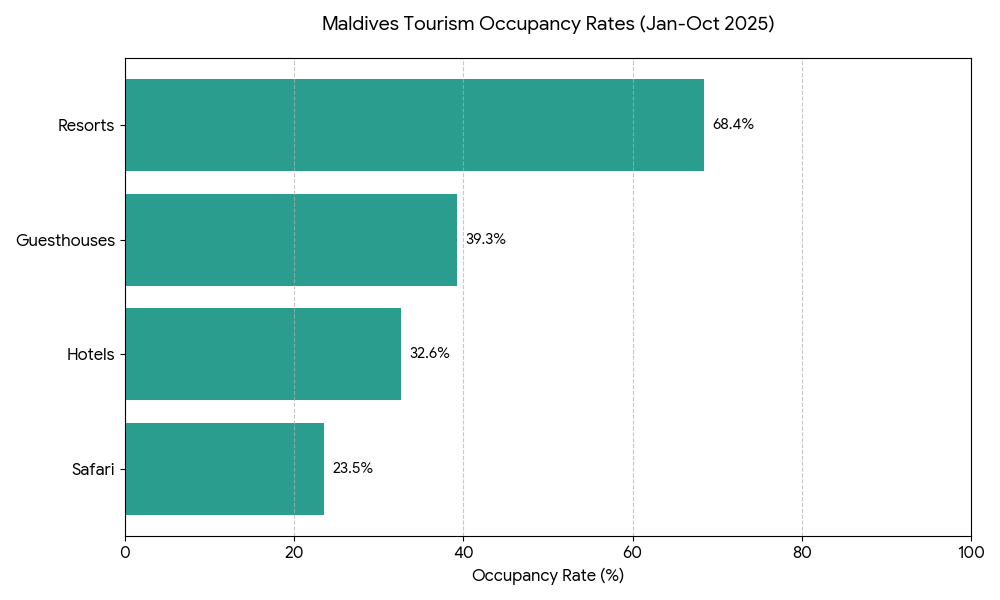

Our current trajectory is unsustainable. We are adding bed capacity at unprecedented levels, yet our occupancy rates tell a sobering story. As of late 2025, our total capacity has reached 67,361 beds, but we aren’t filling them:

In 2024, our overall annual occupancy was just 59%, meaning we operated 41% below capacity. Despite this, we have added another 3,000 beds this year alone.

When growth is driven by bed count without a corresponding increase in utilization, we see a race to the bottom: operating costs rise, and price-per-room drops. We have to ask the tough questions: What is the actual value we are generating per bed, per worker, and per island?

The data is clear: we are building a massive infrastructure that we are failing to fill. If we continue to expand our bed capacity without modernizing our regulatory framework, we aren’t just wasting investment. We are setting our tourism sector up for a slow-motion decline.

My advocacy for these changes is not a departure from my faith or our shared values. Rather, it is an appeal for transparency over hypocrisy. We currently tolerate a “floating bar” system that exists in a legal gray area, encourages black-market activity, and denies our capital’s premium hotels a fair chance to compete.

Progress requires us to be more than just builders of resorts; we must be architects of a modern, competitive economy. It is time for a serious, high-level dialogue between the government and the private sector to bridge this gap. We can no longer afford to let the 41% of our empty beds remain silent.

The question is no longer whether we should have this debate—the question is how much longer we can afford to wait.